How are Pride celebrations, which commemorate the anniversary of the Stonewall Rebellion, linked to Canada day, which marks the anniversary of the Constitution of 1867? They share an open secret: the state’s control of sexuality/gender and the state’s control of land are two of the cornerstones of colonization. And it’s no coincidence that the resistance movements they are connected to draw deeply from the leadership by Indigenous women, women of colour, and people whose genders don’t fit well in the binary model that is dominant today.

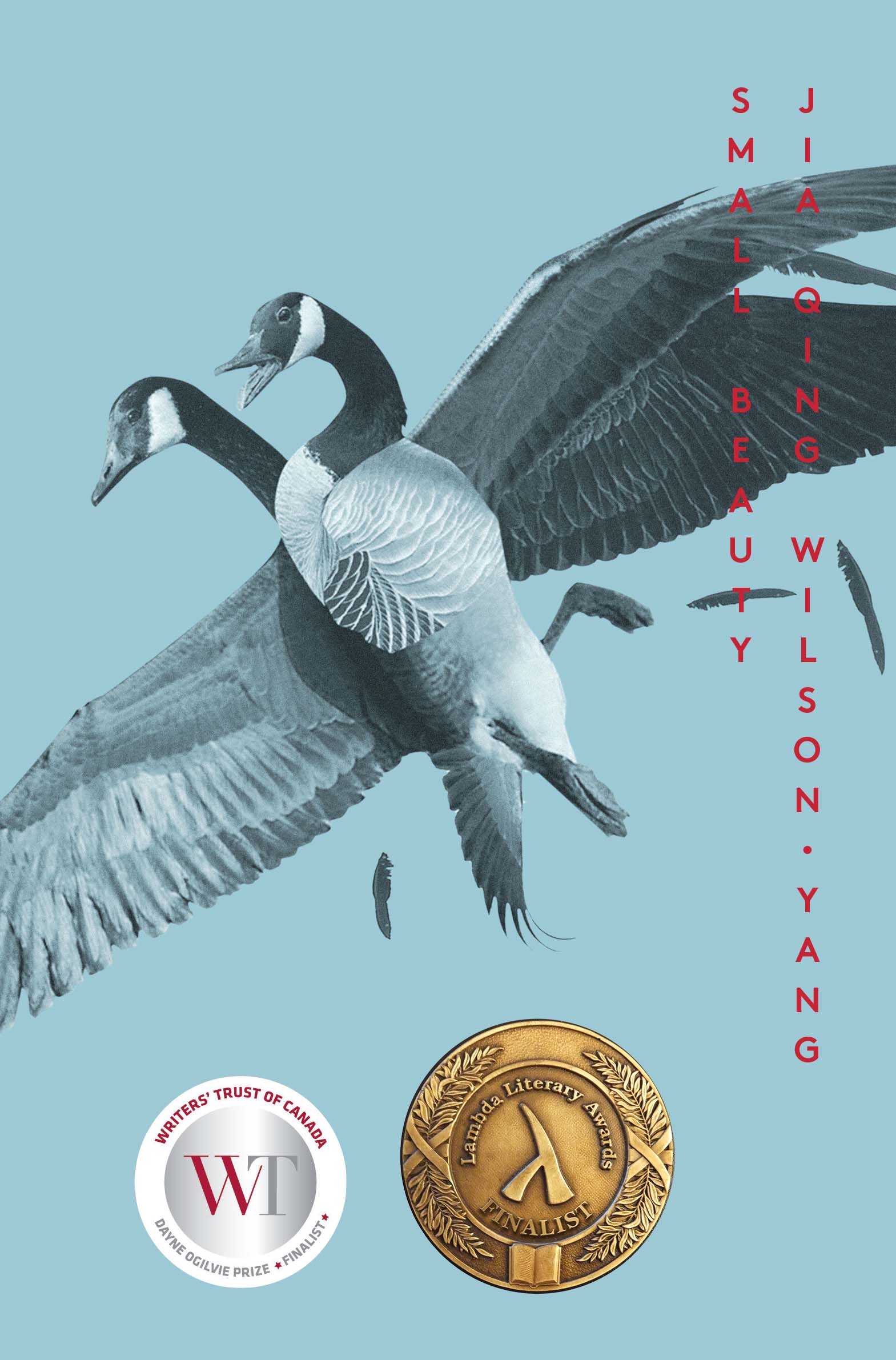

Photo of jia qing wilson-yang from Metonymy Press

In this interview, take a trip with award-winning, Quaker-influenced author jia qing wilson-yang as she exposes the connections between these ideas in her own life, offers suggestions for the path forward, and beautifully welcomes all of us to explore for ourselves.

As you read, here are some queries you might find fruitful. Does this article inspire other questions for you? Please leave them in the comments!

Queries

- What role has silence played in losing connection with my ancestors, or re-weaving that connection, or both?

- How, in my experience and for those around me, has sexuality and gender been used for colonization, or for liberation?

- How, if at all, do I experience the relationship between pacifism and profit-making?

- What works best when I am helping someone question long-standing beliefs? What have others done to help me question mine?

- What is my relationship to punishment and/or penal abolition, in relation to prisoners, people of colour, people with intellectual disabilities, children, and others?

- When have love and faith helped me participate in healing, and when have they become “internal noise” that prevents me from hearing someone whose experience is different from mine?

- How have faith communities related to state control of land, of gender, of sexuality? What is the role of today’s faith communities in moving that relationship towards justice?

Interview

“The biggest project of gender education that ever happened here is colonialism.”

That’s where the conversation ended up when I invited jia qing wilson-yang to talk with me about spiritual practice, sexuality, gender, and her experience growing up Quaker as a mixed-race trans woman.

It’s not where the conversation started. jia qing was in Wolfville, NS last fall for the launch of her book, Small Beauty, which recently won the 2017 Lambda Award for transgender fiction. She currently lives in Toronto, and her spiritual practice includes meditation, learning about Taoism, and pouring a cup of tea each morning for her ancestors. But as a child growing up outside of Hamilton, she attended Quaker Meetings and spent summers at Quaker-run Camp NeeKauNis.

My name is Mylène DiPenta. I grew up in Dartmouth, NS, a gender-unruly child in a white Catholic family where immigration was a living memory. Where jia qing moved toward the city, I moved away – to a village of 700 people in the Annapolis Valley. She drifted away from Quakerism; in my late 30s, I drifted toward it. Over three meals in October 2016, I interviewed her about connections between spiritual practice, gender, sexuality, and colonialism.

What was your experience with Quakerism like?

I remember going to Young Friends retreats at Friends House in Toronto. You’ll see it when you’re there – it looks big on the outside but it’s so much bigger on the inside. It was awesome to spend a whole weekend with your friends, run around, drink too much coffee. We had really rad Friendly Adult Presences [adults on hand who support youth retreats]. They were on board with whatever we wanted to do. [Their take on sex was] don’t have babies if you don’t want to, and be safe. We were given a long leash, as long as we cleaned up after themselves.

I wish we had more sex ed, good sex ed, consent[-based] sex ed. I found out about ways that that was lacking years later.

Youth retreats were great – we had them in Hamilton, at camp NeeKauNis, “a place for lost souls.” You definitely feel like you’re in a place where people have had [Quaker] Meetings for a long time. There’s a huge ironwood tree. Ironwood trees are not big, typically, and it has a huge hole in in, like it should be dead, but it’s not, and people have worship there.

I started going to camp when I was six. It was great, I loved it. It was the first time I spent time around a lot of kids. Obviously I went to school, but that sucked. The first few years, the whole family would go. As soon as I was old enough to be [hired as] staff, I was there every summer until I was 18 or 19. After that I went to the Thanksgiving retreat. Being there in the autumn was great, to look out on the bay. [It had that] intentional community feel that happens when you’re with a group of people [consistently over the years].

I could feel it in my body if I didn’t go [to Camp NeeKauNis] for a year… It wasn’t a sense of ownership, more of a sense of belonging. I need to go somewhere I belong.

I got to hang out with my friends, feel like I had a sense of independence. I could feel it in my body if I didn’t go for a year, I felt a little out of sorts. It wasn’t a sense of ownership, more of a sense of belonging. I need to go somewhere I belong. I needed that because I was a mixed-race kid in a mostly white town, and trans and queer, but those things were not things I was aware of at the time.

Did you incorporate your Quaker experiences in your novel?

I did write about the camp in the novel. Anyone who’s been there would know. The main character in the novel breaks into the boathouse and steals a canoe. I never did that! But I definitely thought about it.

What is your spiritual practice like now?

When I started telling the world I was trans and being open about who I like to sleep with, I wasn’t so much in [touch with Quakers.]

I went back to Quaker [Meeting occasionally] and it still felt like a really white space. That’s not something I need a lot of right now. Not that I don’t love Meeting. I was part of a queer people of colour meditation group in Toronto; that was really great. Having meditation with queer folks of colour – just to hold that space was fantastic. I really crave that silence. The silence is so ingrained in my routine, being comfortable with silence [when so many others aren’t.]

The story of George Fox … How was it that he decided to do something that most white people were not doing, but lots of Buddhists were?

The story of George Fox – it was always presented to me as, [direct revelation] just occurred to him one day. But was this idea floating around? How was it that he decided to do something that most white people were not doing, but lots of Buddhists were?

It was lovely [to realize] that there’s a tradition of silence that my mother [who is white] entered. My dad [who is Chinese] went to Jesuit school as a kid in Hong Kong and didn’t have that same connection to Buddhism. But seeing the similarities [between Buddhist and Quaker practices], knowing that that was how my chingbu [grandmother] understood herself, it was a nice surprise to find these things that brought together different parts of my life. I didn’t realize that until I was spending time meditating with other folks of colour. [These days I’m] learning more about Taoism.

When I’m at home, every morning I make tea, pour a cup for my ancestors… ask for their watchful eye to continue. I try and feel [their] presence.

When I’m at home, every morning I make tea, pour a cup for my ancestors, light incense, pray to a small altar I made with their names written up and things that remind me of them, give thanks, ask for their watchful eye to continue. I try and feel some kind of presence that I don’t necessarily attribute to a god or a higher being, but more about ancestors. That feels genuine right now. My chingbu is buried in North York; I clean [her grave], light incense, leave papaya. My dad doesn’t remember tons about traditional Chinese worship, so I feel like I’m learning.

Reweaving that connection to your ancestors brings us to the connections between colonialism and spirituality. Do you want to say a bit about that?

As I’ve been learning more about ancestor worship, I’m also thinking about how my white family is implicated in colonisation. That’s just a natural connection. Who are these people I’m worshiping? Why am I paying respect to them? It’s never been a question, that that’s what I should do. But, what did we do?

Who are these [ancestors] I’m worshiping? … It’s never been a question, that that’s what I should do. But, what did we do?

My grandmother[‘s family] came into Canada as Loyalists. They settled in Brantford, 7 or 8 generations ago, right beside Six Nations, the largest reserve in Canada, one of the largest residential schools in Canada. This is on my family[‘s heads]. They were Anglicans in Brantford. Even if they weren’t working at the school, because it was run by the Anglicans and Brantford isn’t that big, I refuse to believe that we’re not implicated. Brantford and other nearby towns have a long history of encroaching on the reserve.

[The needed] healing work has to be about spiritual practice. My partner is mixed Indigenous. We had a marriage ceremony a year ago, we’ve been together 8 years, I feel very committed to her. This person I have a great deal of love for in a very complex way, has been really negatively impacted by colonization, while my family has definitely benefited [from it] and played a role.

The times that I spent a lot of time in activist communities, most of my 20s in different cities, around a lot of anarchists, something that I always felt was lacking in our organizing was faith or love or something really positive. There’s so much anger. Justifiable anger makes a lot of sense to me; anger can be so useful as an emotion, [but it] can be toxic when not balanced — it can eat you. I’m trying to conceptualize the work that we’re doing as part of a larger healing process.

Sex and gender injustice are a big part of how colonizing gets done. What are your thoughts about that?

Targeting a gender system is a way to destabilize a society. So if we’re going to talk about gender in Canada, that means “Decolonizing transgender 101.” The biggest project of gender education that ever happened here was colonialism.

When we think about settler colonialism – Gord Hill, [a member of Kwakwaka’wakw Nation] from Vancouver, gave a great presentation. [He talked about the] brutal history of settlers, Spanish colonizers coming into California. Anything that looked like 2 men having sex, anything that is read as a transgression against masculinity is really violently punished. This is documented in paintings. They see people they’re calling “joyas,” [who they think are] men in female dress in relationships with other men. But they’re actually other genders that are maybe neither male or female. There are many different words used to describe those genders/practises, depending on what nation they’re part of.

…we talk about North America as this hub [of progressiveness but] now the Asia Pacific Transgender Network uses standards of health from the [US-based] World Professional Association for Transgender Health. Targeting [another culture’s] gender system is a way to destabilize a society.

So often when we’re talking about trans identities, we talk about North America as this hub [of progressiveness]. All of the words we use – trans and non-binary, are still [rooted in European ways of thinking.] Now the Asia Pacific Transgender Network uses standards of health from the World Professional Association for Transgender Health [WPATH – which is US-based and rooted in Euro-Western scholarship] to do education about trans identities in Nepal and the Philippines and Pakistan.

And we can trace it back to a boom in population in England around the time when industrialization is happening – capitalism is taking off – [because the authorities have criminalized sex that isn’t procreative.]

For Chinese folks, because of Confucius, there’s been patriarchy and a binary gender system for thousands of years. There are some small references to people born as boys raised as women to perform wu shamanistic functions, but that was thousands of years ago. Bringing that together for myself, it’s about being on the land, and thinking about what it means to be descended from the people I am. I begrudgingly don’t have another lens through which to look at it. I would love it if I did but it wouldn’t be mine.

I identify as a gay lady; I feel great about it. It feels right. I have deep respect for other trans women … that’s where I am. Such massive deep respect for older trans women. How did you survive? What kinds things did you do? That’s amazing to me.

It could only happen in a context of colonization that I could be meeting all of these trans women. We’re sort of mashed in together because they don’t have words for us. It’s usually problematic, but it does bring together people who have a shared experience because they’re punished by patriarchy in a very particular way. Shared experience can be grounding.

What started you on the political path you’re on?

I grew up in a [Quaker] Meeting! I had an amazing Sunday school leader – Helen Brink, who recently passed away. She would bring in articles for conversation about disarmament, environmental issues, get us thinking about social justice. I was 10 at the oldest when I remember really taking that to heart, that being a big thing. Then I was going to rallies and peace marches as a teenager because the Iraq war was happening, going to school in Guelph, getting involved in anti-capitalist organizing on campus. That’s when I started to think about violence differently – people think that being a pacifist means being against physical violence, but I was starting to think about structural violence, about poverty as a kind of violence. And thinking about decolonization and self-determination. I went to a conference in Montreal, called Land, Self Determination, and Decolonization. There were Indigenous speakers from across the country, talking about the Gustafsen Lake standoff [on Secwecmec/Shuswap territory]. They didn’t want it to be an armed conflict but felt it was necessary. I listened to Mohawk speakers talk about the Oka crisis.

[Quaker] Sunday school [got] us thinking about social justice.

I was hearing these things that seemed almost unbelievable about Canada, based on what I knew.

I was supporting Grassy Narrows through the Rainforest Action Network, trying to raise money. There were a lot of people organizing around Indigenous Peoples Solidarity Network. I helped work on a land reclamation project at Caledonia. I was listening to old Six Nations folks tell stories at night about the pass system on the reserve – what I now know as Indian Act Policies.

What inspired to you write a novel?

I wanted to be a writer since I was a small kid. Some friends started a small press and put out a call for manuscripts. I had a bunch of little bits of writing floating around on my computer. I thought they could come together into one story that was never finished. They said yes – finish writing it.

As a kid, it spoke to me because you could just make everything up. That’s awesome. I loved reading., and I spent a lot of time alone. I was always imagining worlds and scenarios and fights.

What’s your next writing project?

Another book is slowly emerging. I really want to think about responsible ways for settlers to be writing about colonization. I want to talk about prisons. Lots of people I love a lot have been inside at different points. A close friend was jailed for a year, and I would visit her. It wasn’t the first time I did prison support for her but it was the longest she was put away.

So many of the trans people I know have been in jail – they get arrested for sex work or possession.

I really want to think about responsible ways for settlers to be writing about colonization. I want to talk about prisons. So many of the trans people I know have been in jail…

There’s a course on Women, Criminalization and Madness at the Vanier Center for Women [a prison in Ontario]. The students are half social work students and half inmates. Everyone gets the same university credit. This was really problematic but I learned so much. One of the correction officers gave us a tour of the prison. We’re in someone’s personal space, they don’t have a choice, it feels very invasive, but it means I saw the whole prison. The “yard” for maximum security is a concrete room that has a thick mesh razor wire. A concrete room with no ceiling. This isn’t one of the “Supermax” facilities, it’s one of the smaller ones. We walked past the solitary, that’s where trans people go. In Ontario if you haven’t had bottom surgery, I asked a correction officer what happens. You can go to a women’s prison, but you go to solitary. It’s terrifying, inhumane.

I was working with lesbian, gay, bisexual, and trans youth with intellectual disabilities. Three institutions in Ontario were used as asylums for people with intellectual disabilities. Very much a prison kind of institution. They’re also laid out in ways similar to residential schools. Kids were dropped off when they were 2, 4… and stayed their whole lives or into their 20s. There’s a laundry list of horrible abuses. The prison, while physically very different, had similar problems. The correctional officers were complaining that there was no air conditioning… which is true, but you’re going home.

Going there and touring that institution… Lots of those youth I worked with, had circumstances been slightly different, could have ended up there. Working with adults who were survivors, doing a lot of soul-building kind of work, walking through that institution, it was awful. Being there, being able to walk through it – the gravity of it was so different.

What’s the education work you’re doing now?

[At the time of this interview, I was working as the Training and Education Facilitator at Rainbow Health Ontario. Unfortunately, very recently I’ve had to leave that position to prioritize finishing my degree. ]

I was excited to get to work in a more focused way on education. I was interested in working on ideas of transmisogyny, colonization, racism, having those ideas sink in.

…you don’t need to understand something to respect it. I don’t expect that in our day long workshop [about queer and trans issues], a group of people who haven’t considered racism and gender are going to develop this in depth analysis… My job is to make sure they give safe and responsible care to trans and gender nonconforming people.

In the trainings we do, we emphasize that you don’t need to understand something to respect it. I don’t expect that in our day long workshop, a group of people who haven’t considered racism and gender are going to develop this in depth analysis that’s going to influence the work they do. And that’s not my job. My job is to make sure they give safe and responsible care to trans and gender nonconforming people. We give lots of example and role plays. A lot of that means picking one or two simple ideas, [and telling someone that you can] repeat this to yourself over and over. We try to have that be a thing they can take away. That’s all we can hope for. My new boss does a bunch of evaluations and surveys before and after. Ten percent of what they learn happens during training; the rest happens after, when they develop the confidence to start [applying the ideas].

The training itself is just an introduction of an idea. After that you have to do your homework. You want them to be warmed up to the ideas so they go home and learn about it.

What advice do you have for those of us trying to do social justice education?

Find the people who want their organizations to change – find them and support them.

Find each other. Talk to each other. Talking to other trans people about what places fucked them over, what places are really good, saved me a lot of unnecessary trauma and bullshit. There’s enough of that – you don’t need more. Connect with each other. [The organization is] not going to tell you, but maybe someone else got paid a bit more [than you did] one time.

It’s harder to turn down a group of people who are saying, this is a valuable thing, than to turn aside a singular person.

What advice do you have for trans and gender-non-conforming people trying to bring that perspective into a Quaker context?

Quakers already have an understanding of truth as a changing thing – a thing that should change. Faith and Practice gets updated because it needs it. They also have ideas about Inner Light, the importance of the personal journey, and the practice of listening to your own truth from a deep place.

Quakers already have an understanding of truth as a changing thing – a thing that should change… They also have ideas about Inner Light, the importance of the personal journey, and the practice of listening to your own truth from a deep place. But it’s scary to apply that to gender.

But it’s scary to apply that to gender. When you talk about [gender-affirming surgeries] that are permanent, that’s when it becomes real to [cisgender] people. It shakes them in a way they didn’t think they could be shaken. This is not a thought exercise, not philosophical. Friends and family sometimes told me I was being irresponsible.

It has to do with what happens when my deep listening challenges their deep listening. Their listening tells them that there are things that shouldn’t happen. People sometimes reacted with disbelief. “Are you sure you want this? What a terrible thing. You shouldn’t do that to a healthy organ.” As if it’s a really awful thing that will damage you. Well, I’m going to make a new healthy organ. But it shakes people.

It has to do with what happens when my deep listening challenges their deep listening… They were so worried for my well being that they couldn’t hear me. That’s how love can be a kind of internal noise.

Sometimes women who were feminists seemed upset because “we gave you these examples” of how you didn’t have to have a certain kind of body to do anything. [When people found out about my plans for medical transition], lots of Quakers approached me on their own, very sincerely. They were so worried for my well being that they couldn’t hear me. That’s how love can be a kind of internal noise.

For Quakers new to trans issues, this is about applying old skills in new contexts. Training on trans issues can help demystify the misconceptions. But we can also reassure people: “You already know how to do this. Be there. Make a casserole.”

Looking for More from jia qing?

Check out her award-winning book Small Beauty, published by Metonymy Press!

Breastfeeding Friendly Organization

Breastfeeding Friendly Organization